New Year’s Post Cards

When a foreigner said “Happy New Year” to me at the end of December, I found it odd. In Japan, this greeting is reserved for use only after January 1st. This small cultural difference reminded me of nengajo—Japan’s New Year’s postcards—a tradition deeply rooted in our holiday celebrations.

Tradition of Nengajo

In Japan, there is a long-standing custom of sending nengajo to arrive precisely on January 1st. These postcards typically include standard New Year’s greetings, updates on recent activities, expressions of gratitude for the past year, and hopes for the coming year. They are often decorated with the zodiac animal of the year (this year, it’s the snake). Over time, nengajo have become an integral part of Japanese culture, exchanged not only between individuals and families but also among companies and organizations.

Hisotry of Nengajo

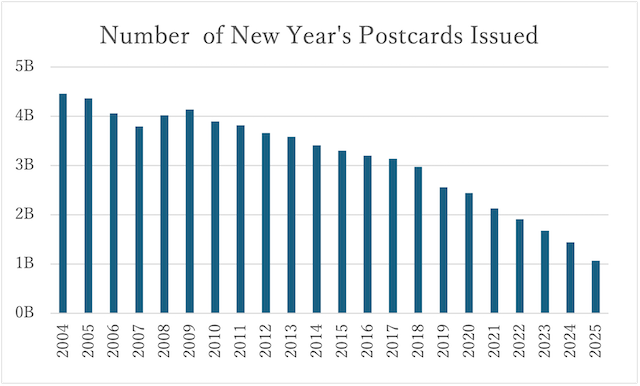

The history of nengajo is said to date back to the Heian period (794–1192). However, the origin of their modern form can be traced to the Meiji era (1868–1912), when Japan established a modern postal system. Initially, people either wrote them by hand or ordered them from print shops. In the late 1970s, the introduction of a simple home printing device called “Print Gocco” led to a significant increase in the number of postcards issued. Later, the ability to print photos on postcards made nengajo a convenient medium for sharing updates on children’s growth once a year. With the widespread adoption of personal computers, high-quality printing became possible at home, and address printing became automated, further boosting the number of New Year’s postcards issued.

At its peak in 2004, an astonishing 4.45 billion nengajo were issued. Considering Japan’s population of around 128 million at that time, this number is remarkable. During this peak period, delivering such a massive volume of postcards required additional workforce, and many high school students worked part-time to assist postal workers.

Decline of Nengajo

However, the popularity of nengajo has steadily declined. This year (2025), only 1.07 billion nengajo were issued, and this number is expected to decrease further in the future. Several factors have contributed to this decline:

Digital Communication: The rise of email and social media platforms like LINE offers more convenient alternatives.

Economic Factors: This year’s sharp decline was partly due to a postage fee increase, rising from 63 yen to 85 yen, making digital communication even more appealing.

Generational Shifts: Many younger people no longer see the need to send nengajo. On the other hand, there are quite a few elderly people who have grown weary of maintaining formal relationships.

Practical Barriers: Privacy concerns have led schools to stop providing student directories, making it difficult for students to exchange nengajo.

Emergence of Nengajo-Jimai

Another significant trend this year is nengajo-jimai, where people declare in their nengajo that it will be their last year participating in the tradition. This is especially common among older generations, who are organizing their affairs later in life. For some, this decision comes after decades—sometimes 50 or 60 years—of exchanging nengajo with friends or acquaintances they no longer meet in person.

The term “nengajo-jimai” reflects a sense of closure. While many people include messages expressing hope to stay connected via email or social media, in reality, this often marks the end of the relationship. As purely symbolic exchanges are reconsidered, some feel it is time to let go.

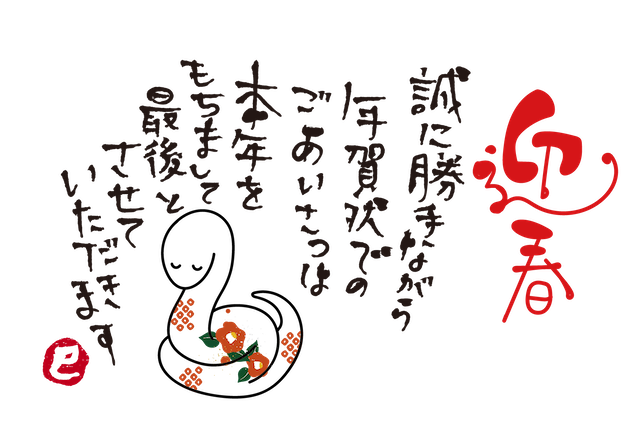

An example of a nengajo-jimai message:

The card reads, “I regret to inform you that this will be the final year I send New Year’s greetings via postcards.”

Personal Reflection

This year, I experienced nengajo-jimai firsthand with my former middle school teacher, now in his 80s. For over half a century, we exchanged nengajo. This year, his message read:

“As part of my life organization, I have decided to end nengajo exchanges. Thank you for your long-lasting connection.”

Reading those words filled me with a deep sense of sadness, as it reminded me of the years he had watched over my growth, year by year. It was a poignant moment, marking the end of a connection that had been quietly maintained through nengajo for so many years.

Future of Nengajo

Nengajo remain an important tradition for many, but as digital communication continues to evolve and the nature of human relationships shifts, their decline seems inevitable. This year appears to mark a turning point, and the number is expected to decrease even further next year. Despite this, nengajo hold a special place in Japanese culture, symbolizing gratitude, connection, and hope for the future. Even as this tradition fades, I hope that the memories and bonds it has nurtured will endure.