In a conversation with a guest, he mentioned that the movie “Lost In Translation” (2003) had sparked his interest in Japan. While I was familiar with the title, I hadn’t watched it yet, so I promptly viewed it. It was an interesting movie. It made me think about a lot of things.

The story revolves around an American movie star (Bill Murray) who, while in Tokyo for a whiskey ad shoot, gradually becomes drawn to a young woman (Scarlett Johansson) he meets by chance at the hotel. Though they are of different ages, they share a commonality in feeling a sense of emptiness beneath outwardly happy lives.

The setting of the two characters’ story reflects Tokyo at that time. Against the backdrop of a modernized city, the film captures the spirit of the era. Shibuya Crossing, Game Center (arcades), bars, pachinko parlors, karaoke, and even television variety shows are depicted. Furthermore, the movie portrays not only Japanese culinary traditions such as sushi, shabu-shabu, and sake but also scenes from the hospital waiting room. Despite its modernization, there’s a sense of foreignness and an inexplicable unease that can’t be grasped through words.

The sense of unease extends beyond the visible aspects of the city to the psyche of the Japanese people. While somewhat stereotypical, the film depicts the difficulty in expressing emotions among Japanese, making it challenging to discern their thoughts. Additionally, it portrays Japanese speakers struggling to distinguish between “R” and “L” sounds, resulting in awkward English. (This is a challenge I personally face constantly as well.)

While these Tokyo scenes might have seemed ordinary to Japanese viewers, they were likely more striking to foreign audiences 20 years ago. Moreover, this film’s portrayal of a mysterious Japan likely enchanted many foreigners. Subsequently, it’s surprising for many Japanese people that Shibuya Crossing became a popular tourist spot for foreigners. Indeed, many Japanese express their inability to comprehend why such things became popular.

More than 20 years have passed since the release of that film. The cityscape of Tokyo has also undergone significant changes. The completion of the 634-meter-tall Tokyo Skytree in 2012 and the ongoing redevelopment, dubbed as a once-in-a-century transformation, around Shibuya Station are notable examples.

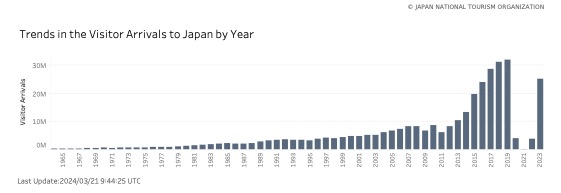

Looking at the graph of foreign visitors to Japan during that time, it becomes evident that over 20 years ago, the number of foreign travelers from overseas was less than one-sixth of the peak number (2019). There was a temporary decrease after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, triggered by the Fukushima nuclear disaster, but it sharply increased afterward. This trend has continued until today, except for a significant drop during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nowadays, you can hardly find a major tourist spot without foreign visitors. Moreover, there is also an increasing number of people who want to revisit Japan, and among these repeat visitors, many seek non-touristy places. Additionally, there is a growing expectation for tourism that involves participation and experience rather than just sightseeing and shopping.

Recently, a French designer acquaintance contacted me, asking for connections with suiseki craftsmen because he wants to learn more about suiseki. Suiseki? It’s like miniature bonsai but with stones instead of plants. Embarrassingly, I didn’t know that term. Wanting to help, I started researching and discovered the unexpectedly fascinating world of suiseki. I learned about Japan from someone abroad.

There’s much value in foreigners rediscovering various aspects of Japan that Japanese people may not have noticed. However, the deeper layers of Japanese culture, which cannot be fully understood through tourism alone, continue to expand infinitely. One might even call them areas that remain incomprehensible even through translation.

It’s indeed intriguing how the various aspects of Japan depicted in the movie “Lost In Translation” have sparked an interest in traveling to Japan. However, the lingering sense of unease about whether differences in language or translation can truly bridge the gap in culture and human relationships feels like a fundamental question.

I believe that conveying the deep facets of Japanese culture, the faces hidden behind the masks, to foreigners is an important task for tour guides.